Lawrence Diehl Brown

|

Medieval Swordplay

Published Feb 21, 2024. L Brown, author.

For the descriptions of swordplay in my first two novels, The Colors of Fire and Of Princes and Kings, I relied on three sources. The first was my years of fencing with the team at The Ohio State University. The second was a course I took in theatrical swordplay (in order to learn what NOT to do), and the third was original sources. The oldest surviving manual on western swordsmanship dates back to the 14th century, although historical references about fencing schools are found as early as the 12th century. Historical fencing manuals from 1300 to 1500 and beyond can be found online (https://www.thearma.org/manuals.htm).

For the descriptions of swordplay in my first two novels, The Colors of Fire and Of Princes and Kings, I relied on three sources. The first was my years of fencing with the team at The Ohio State University. The second was a course I took in theatrical swordplay (in order to learn what NOT to do), and the third was original sources. The oldest surviving manual on western swordsmanship dates back to the 14th century, although historical references about fencing schools are found as early as the 12th century. Historical fencing manuals from 1300 to 1500 and beyond can be found online (https://www.thearma.org/manuals.htm).

Swordfighting in movies is usually entirely unrealistic. The fights are choreographed to look good for the camera. The duelists typically make wide swings with the sword or spin around in a move that would have left them completely unprotected. In ancient times, actual battles with swords would have been very short. They would end after a few moves when a hit to the body was achieved. This could eventually be fatal, owing to the lack of disinfectants and good medical treatment at the time. If a minor hit to the body occurred, the fencers would disengage and engage anew. If they were fencing without armor, the way we often see in movies, the first hit would almost certainly end the bout. Armor was for keeping the enemy from scoring a fatal hit on an unprotected part of your body, so blocking every blow was not part of regular swordplay. The armor took care of that.

Swordfighting in movies is usually entirely unrealistic. The fights are choreographed to look good for the camera. The duelists typically make wide swings with the sword or spin around in a move that would have left them completely unprotected. In ancient times, actual battles with swords would have been very short. They would end after a few moves when a hit to the body was achieved. This could eventually be fatal, owing to the lack of disinfectants and good medical treatment at the time. If a minor hit to the body occurred, the fencers would disengage and engage anew. If they were fencing without armor, the way we often see in movies, the first hit would almost certainly end the bout. Armor was for keeping the enemy from scoring a fatal hit on an unprotected part of your body, so blocking every blow was not part of regular swordplay. The armor took care of that.

An exception to the typical short bout would occur when the opponents were evenly matched. A fight could go on for a long time, until the combatants tired and called it a day, or until one of them made a fatal mistake.

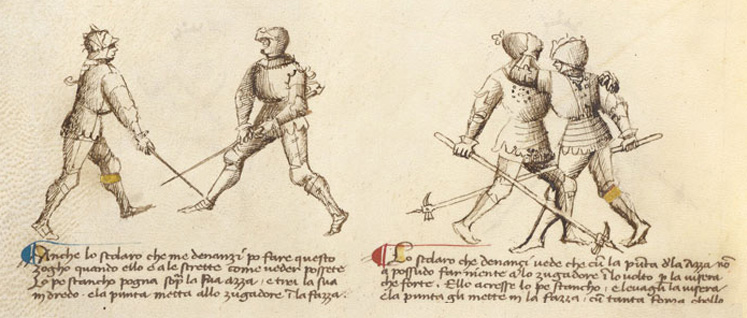

The earliest works to describe swordplay indicate how sophisticated and well-planned it was. The combatants developed an ability to guage timing and distance to make the sword’s cutting and thrusting capabilities more effective. It was nothing like the contained, precise movements of modern foil fencing. They practiced the footwork of a boxer and the grappling, kicking, and throwing techniques of a martial artist. The armored glove on a left hand could be used to seize a blade and hold it while the right hand made an offensive thrust. There might be stomping, tripping, or throwing the opponent.

The earliest works to describe swordplay indicate how sophisticated and well-planned it was. The combatants developed an ability to guage timing and distance to make the sword’s cutting and thrusting capabilities more effective. It was nothing like the contained, precise movements of modern foil fencing. They practiced the footwork of a boxer and the grappling, kicking, and throwing techniques of a martial artist. The armored glove on a left hand could be used to seize a blade and hold it while the right hand made an offensive thrust. There might be stomping, tripping, or throwing the opponent.

Every attack was planned out, and might include an expectation of a block, a counterattack, a feint to draw out the opponents sword and another attack. The winner would typically be the better trained fighter. Anger in a contest, typically shown in the movies to make a fighter win, would militate against this strategy and certainly cause the fighter to lose. The most successful knights, like the famous William Marshal, would keep a cool head, focusing on discipline and training.

Bibliography

The Knightly Art of Battle, Ken Mondschein, 2011, 128 pages, 93 color illustrations, ISBN 978-1-60606-076-6, Getty Publications, Imprint: J. Paul Getty Museum.

Medieval Combat — A fifteenth century manual of swordfighting and close-quarter combat. Hans Talhoffer's professional fencing manual of 1467. January 2000. Greenhill Books. ISBN: 1853674184.

Gladiatoria Dierk Hagedorn & Bartlomiej Walczak. A group of German fencing manuscripts from 1450. Includes several editions of a treatise on armoured foot combat, specifically aimed at duel fighting. 2018. Greenhill Books. ISBN 9781784383336